Listening to Ma

Sound, Space, and Civic Tech in Japan

Podcast in English: July-August 2025

The Japanese word for “space”, 間 (ma), carries layered meanings. It can be translated as “interval”, invoking the space between two or more things, which can be both spatial or temporal in nature. In Japanese cities, sound and civic technologies play a role in how this interval is produced, navigated, and governed.

Das japanische Wort für “Raum”, 間 (ma), trägt vielschichtige Bedeutungen. Es kann als “Intervall” übersetzt werden und verweist auf den Raum zwischen zwei oder mehr Dingen, die sowohl zeitlicher als auch räumlicher Natur sein können. In japanischen Städten spielen Klang und Civic Tech eine Rolle dabei, wie dieses Intervall hervorgebracht, erfahrbar gemacht und gesteuert wird.

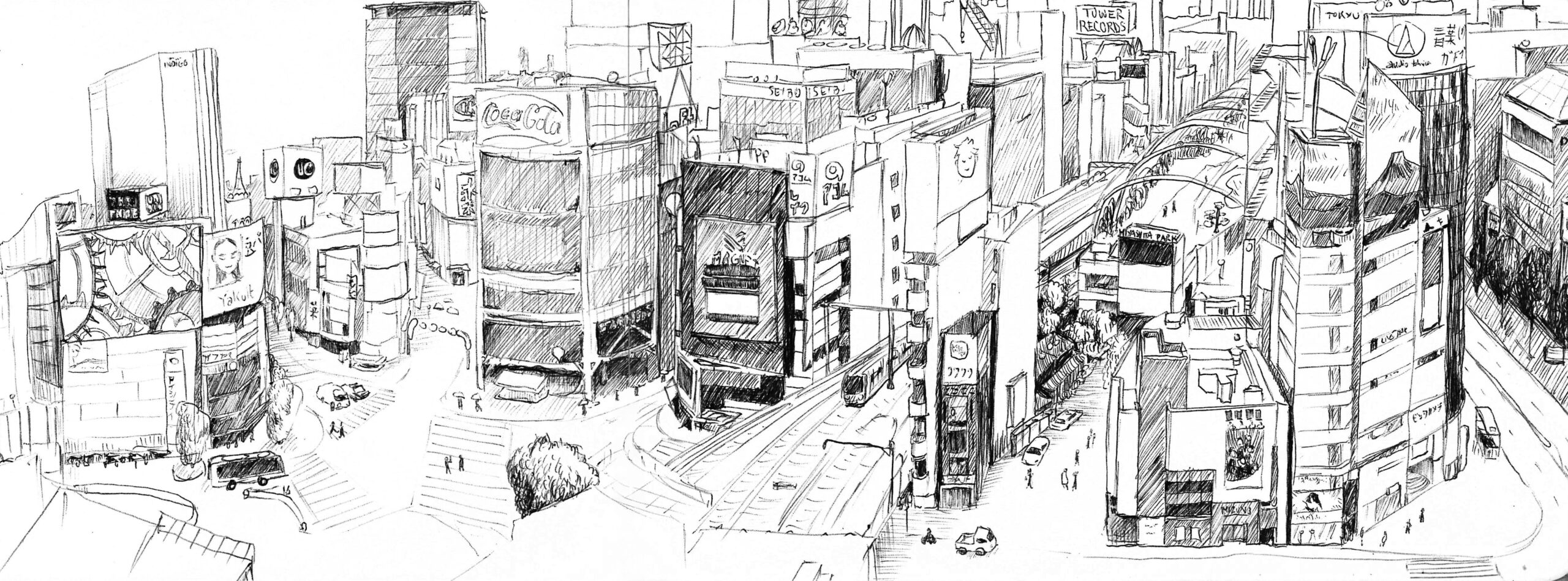

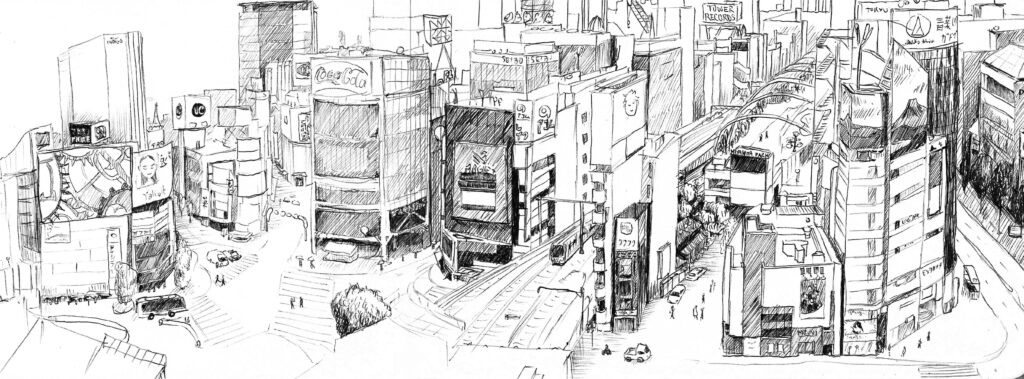

Flaneurs of Japanese cities may notice these different ways that ma is defined and made legible: through dense layers of visuals, but also sound.

Japan’s urban soundscape is famously distinctive. Cicadas fill the summer air like cosmic background radiation. Train stations signal arrivals and departures with distinctive melodies. Pedestrian crossings chirp and click in specific patterns. Convenience stores greet you with jingles that linger in your mind, long after you’ve left the country. At first, the density of sound can feel overwhelming. But over time, there is something orienting, almost calming about it.

During a workshop with researchers and civic tech practitioners at the University of Tokyo, the term civic pride surfaced repeatedly. Unlike in Germany or the United States, it was described as a central aim of civic tech initiatives in Japan, especially outside major cities.

Civic pride is a very popular topic in Japan, especially in rural areas, because younger people tend to go to Tokyo, Osaka, […] and [members of the civic tech community] try to find that interest in connections with the local community.

Yuya Shibuya, August 2025

Sound, it can be argued, plays a subtle role in cultivating that attachment: anchoring everyday movement to place, memory, and local identity.

Consider eki-melo, the short melodies played at train stations. Originally introduced to soften the harsh sounds of bells, they spread widely after the privatisation of Japan’s railways in the late 1980s. Today, many stations have unique tunes tied to local history, popular culture, or nearby landmarks. These melodies become cues you recognise, a feeling of identification that is deeper than a single sense could elicit.

Pedestrian crossings use two distinct patterns to indicate whether the north-south or east-west crossing is currently green. Bird calls mark station exits, originally designed for visually impaired passengers but useful to everyone. Sound is used as a navigational device, embedding orientation into the everyday.

This may appear at odds with common assumptions about Japanese design minimalism. Visually, urban space is often dense with signage, screens, and information. Sonically, it is carefully layered rather than noisy. Both reflect a relational understanding of space: meaning is produced through context, use, and rhythm.

These practices connect to a broader spatial ontology. Space in Japan is frequently understood as event-based rather than fixed (cf. Pilgrim 1986). Scholars such as André Sorensen (2002) have noted that while the physical urban fabric is historically unstable – subject to earthquakes, fires, and redevelopment – the social fabric is remarkably durable. Neighbourhood associations (自治会/ 町内会; jichikai or chōnaikai) and shopping street organisations (商店街; shōtengai) can outlast the physical form of the city.

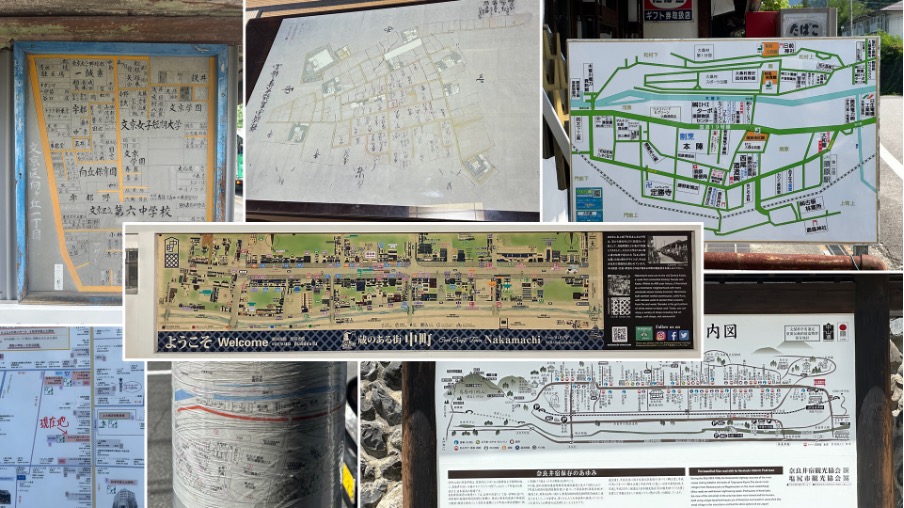

These groups actively produce space. They maintain benches, roofs, decorations, and orientation – again through sight and sound. In Nagoya’s Ōsu district, a shopping street plays a looping jingle, a theme song specifically about that street. Maps produced by these associations tell a similar story: they prioritise lived relations over abstract geometry, often aligning with the viewer’s position rather than north.

This helps explain why “public space,” as an abstract category, plays a weaker role in Japan than in many European contexts. The concept entered common use relatively recently and carries ambivalent connotations, often associated with officialdom rather than democratic openness (Dimmer 2010). Parks and plazas exist, but they are frequently designed for transit rather than lingering. Informal, unprogrammed use, like sitting for lunch or throwing a baseball, is more constrained.

In Japan, for me, public space is not even a concept for a lot of people. […] I feel there’s a lack of public space here, and no one feels it, the society does not feel this lack of public space. Particularly for certain demographic groups, I feel there’s absolutely no public space. […] I went to Europe recently and I just remembered, okay, this is what public space used to mean for me. And when I came here, it changed.

A PhD student at the University of Tokyo, August 2025

Yet this does not signal an absence of civic life. Rather, it is organised differently: through social structures more than spatial symbolism, through tacit coordination rather than explicit regulation. Governance, too, operates more through mutual understanding. Written rules exist, but social norms often matter more. It is common to see people riding bicycles on the sidewalk, even where signage prohibits it.

Civic tech initiatives reflect this relational approach to governance. As Roy Bendor, Associate Professor of Critical Design at Delft University of Technology, put it:

There’s a duality when we think about civic media. On the one hand, it’s a tool of governance. But it’s floated in many cases with a kind of rhetoric of empowerment. And this is something that I think is quite difficult to square.

Roy Bendor, August 2025

A PhD researcher at the workshop reframed this dilemma through the lens of government capacity rather than intention. Reflecting on post-earthquake responses in Mexico City, they noted:

The government is offloading work to civil society … sometimes there’s not even that intention. The government is non-functional in certain areas and then civil society is really empowered – but that’s not a good thing. You’re depending on the fact that there’s some people who want to do good.

A PhD student at the University of Tokyo

Similar dynamics exist in Japan, where much volunteering and later civic tech activity emerged in response to natural disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet the relationship with government is seen differently.

Most of the cases that I met [in the civic tech community], they tried to collaborate with local government… They start from the beginning, have discussions, identify issues together.

Yuya Shibuya, August 2025

It is in this space that Japanese civic tech increasingly operates, not only building tools, but experimenting with forms of local governance: using AI to analyse public sentiment, match volunteers, simulate dialogue, and mediate understanding.

Listening closely to Japanese cities made these differences audible. Quiet side streets in central Tokyo, loudspeakers in tiny villages playing announcements and melodies. The sounds do not always match expectations.

Sound, mapping, and civic technologies are not just there to optimise the city. They provide elements of identification, orientation, and care that create intervals of ma. In the words of Hayao Miyazaki: “The creation of a single world comes from a huge number of fragments and chaos.”

This concludes our series on digital city-making, but the What/Next blog and podcast will continue to put out insights and stories about cities in times of transformation.

This article draws on field recordings, workshops, and conversations conducted in Japan during a JSPS postdoctoral fellowship in July–August 2025.

Yuya Shibuya is an associate professor in the Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies at the University of Tokyo. She researches people’s socio-economic activities, behavioral changes, and digital media activities.

Roy Bendor is the Associate Professor of Critical Design in the Department of Human-Centered Design at Delft University of Technology. His research explores the capacity of design to disclose alternative social, political and environmental futures.